· By Joseph Welstead

5 reasons I ditched my Whoop band

At first there were pedometers. Then came the calorie counters. Today, it’s HRV monitors and sleep trackers. Soon, it’ll be continuous glucose monitors. Are health trackers helpful? Are today’s wearable devices - Oura rings, Whoop bands, Apple Watches & co - helping you live a happier and more fulfilled life? I’ve gone deep into the wearable world, and my answer is firm no. Here’s why.

I’ve spent the past 6 months with a Whoop band around my wrist. I’ll say it loud and clear: it was love at first sight when I received it. The tech is sublime, the app’s UX is second to none, and the data reporting is frankly outstanding. And trust me, I’ve received a lot of health reports in my previous life as a pro athlete.

Whoop bands were the perfect tool for tracking changes to REM sleep using our award-winning night-time supplement Unplug, and I believe they can be of great service in two general circumstances:

- Wearables are great for testing lifestyle changes. If you want to easily know whether Intermittent Fasting, or wearing earplugs at night, or eating red meat, affects how you recover on a daily basis, tools like an Oura ring or a Whoop band are incredibly handy.

- If you have an underlying health condition, and want to track early signs of illness to take prompt action, continuous tracking of your Respiratory Rate (something Whoop offers) may be a cheap and effective early detection tool. Particularly helpful in Covid-era.

Amazing how many messages I’ve gotten like this. Respiratory rate is a v impt measurement right now. pic.twitter.com/Q5XxRhchl7

— Will Ahmed (@willahmed) September 16, 2020

But let’s focus on the primary prupose of wearables.

While Whoop promises you’ll get to “know yourself with 24/7 personalised insights”, a slightly mundane Oura Ring assures “personal insights to empower your everyday”. Meanwhile, Apple Watch has declared that “the future of health is on your wrist” - and it can be yours for a mere £379.

I’ll come clean: I love the idea of tracking our health over time. There’s something incredibly powerful in visualising progress: being halfway up the mountain and getting a clear view of how much you’ve already achieved. But with fitness trackers, you don’t get to choose when to enjoy the view. You’re forcefed data every single day. And in its current form, this amount of data is overbearing, intrusive and obstructive.

Not only is some of the data’s accuracy questionable (we’ll get into that), it’s also highly addictive and causes you to seriously question yourself when you’d otherwise be full of confidence. The inevitable gamification of these repeat-purchase businesses will be a source of anxiety in the same vein as social media. And to top it all off, I’m yet to be convinced of the true benefits of these health trackers for the average user.

A lot to unpack here.

1. The data interpretation is questionable

First up, let’s talk about how Whoop works. Most of the data the app serves is based on Heart Rate Variability - HRV for short. We get into some detail around this in our Whoop x Unplug Experiment. There are some question marks in the scientific community around the veracity of HRV and how much we should read into it - but let’s put that aside since HRV has been used successfully in medical contexts for several decades (see this 1994 study on HRV vs Mortality Risk).

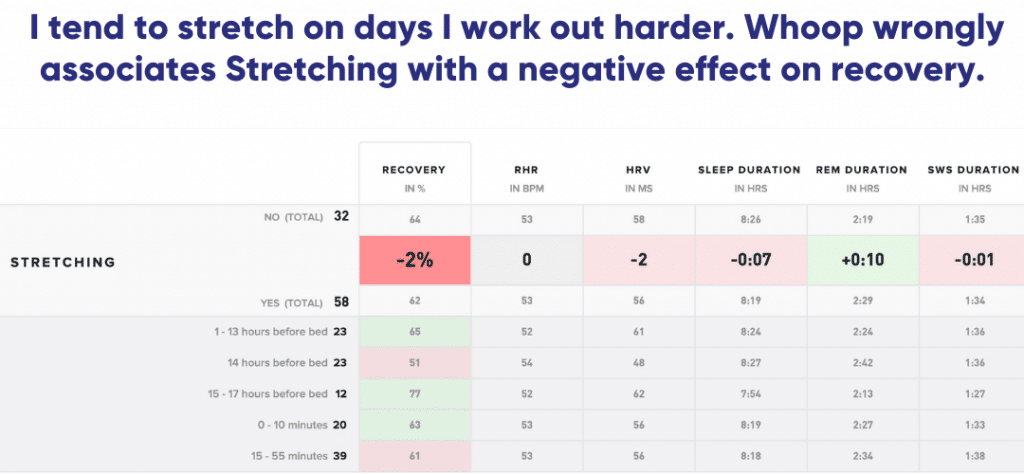

What concerns me more is how much fitness trackers are extrapolating from HRV and furnishing users with oversimplified causations from lifestyle choices. Let’s consider this simple scenario: Jim generally eats later at the weekend than during the week, and inputs this into his Whoop Journal. His monthly performance assessment informs Jim that on the 8 times he ate late this month, his recovery score (based on his HRV) was 12% lower on average than when he ate early. From this, Jim can safely assume that eating late improves his recovery. That’s the way the app presents it, but of course this isn’t the case. The app is incapable - currently - of making simple associations, such as the fact that on the nights Jim eats late, he also sleeps much later into the morning and is less stressed about work: two factors likely to increase his HRV. Nothing to do with eating late after all.

2. Gamification is highly addictive

I truly believe that non-invasive health tracking can be an effective tool for reinforcing positive lifestyle changes. I emphasize non-invasive because this is absolutely not the case currently.

The problem with gamifying data and serving this to users on a daily basis with multiple touch points through the day is clear: it’s highly addictive, in the same way that social media apps are.

You might say that this is exactly what you need to get started, something that nudges you in the right direction every day. And at first, I’d agree with you. But things aren’t always rosey. To make my point, I’ll paint another picture.

Picture yourself waking up on a Monday morning, after a great night's sleep. You wake up feeling good and ready to take on the week. Except you had a few drinks over the weekend and your body doesn’t bounce back as it did when you were 22. So when you check your recovery score, your numbers aren’t great - terrible, in fact. You start to question whether you really do feel great. You should probably take it easy today.

See what just happened? You’ve gone from a high energy, positive mindset, to questioning yourself, before even leaving your bedroom.

And this brings me onto my third problem with health trackers: they’re just another thing we can feel bad about.

3. Your mental health will suffer

If there’s one thing our society is great at, it's self criticism. We even have great names for it: imposter syndrome, insecurity, anxiety, self-doubt. We open our phones to a sea of curated lives, each more beautiful than the previous. We question our very own existence and appropriateness. This is no way to live, and we’re beginning to understand it: just notice how many of your friends are no longer on Facebook.

We’re slowly beginning to realise that social networks might not be so great for our mental health. And yet, we suffer from an impossibly strong shiny object syndrome: according to TikTok’s own data, 17m Brits are spending over an hour a day on the new social media app. But at least we have the hindsight to realise this might not be conducive to societal happiness.

This is not the case with health trackers. We embrace them with open arms. But just a stretch away, just like with social media, we have perfectly relevant historical comparables right before our eyes: calorie counting. In fact, all the way back in 2015 at the height of MyFitnessPal’s usage (over 75m users), Women’s Health Magazine was already recommending its readers to stop counting calories - assuring that removing this cumbersome data tracking would not only give you more happiness and less stress, but in fact help you lose weight: the very reason most people began counting calories in the first place. There have been a flood of similar articles since.

Is more data really what we need?

4. Your social life will suffer

Wearables are great for tracking the effects of a lifestyle change over time. I think we can all agree on this. But frankly, most of these variables are blindingly obvious. Do you need to spend £400 on an Apple Watch to know that wine makes you recover less well? Is it necessary for you to track your sleep cycles in order to know that too much caffeine ruins a good night? We don't need more data, we need more solutions.

At some level, we all know these things. Even so, in the name of fun and socialising, we’ll gladly trade an occasional mild hangover if it means having the best of times with long lost friends. We won’t mind a rare bad night sleep if a shared cuppa is what it takes for our niece to open up to us. These are small tradeoffs for the benefit of our social life and our happiness.

But data doesn’t care for your social life. It’ll remind you so every time you go astray. So what happens to your mental state when you’re celebrating with your family, eating late as a second bottle of red goes round the table? Can you sense that nagging at the back of your mind telling you how bad your recovery score will be in the morning?

Sounds pathetic, I know. But trust me, the thought will be there, somewhere at the back of your mind, whether you’re prepared to admit it or not.

5. Is it really serving those who need help?

Preaching to the converted is easy. But real change is found in helping those who need it most. Helping someone who’s never been able to improve their health despite several short lived attempts. This would be true change, and not an additional gadget for the fittest people on earth. What does it take to create systemic health change in someone’s life? What do you need to do to affect health markers such as Resting Heart Rate and HRV?

These are difficult markers to change. They take time and serious effort. Progress is measured in months, not weeks or days. And here lies a big problem with wearable technology as it currently stands: the data is too much, too quick, too soon. Whoop tacitly incentivises being “in the green”, i.e. well rested. This is a measure of your HRV today, compared to your average over the past couple of weeks. You can begin to see how this might be problematic given that real change takes months. Several weeks of hard training will temporarily push your resting heart rate up and your HRV down, and during the course of this training cycle, your tracker will tell you to rest. So instead of a long period of training which will truly improve your base metabolism, you are incentivised to favour short bursts of training, followed by regular periods of rest. Push beyond this remit, and your app will tell you you’re overreaching and you really ought to take a couple days off.

Without extending to a certain depth of exertion (and therefore bad recovery scores for extended periods of time), you are simply toying with the needle of your fitness level, without ever pushing it upwards.

A final scenario to prove my point.

Picture yourself on the morning of your greatest competition. Perhaps it’s the day of your event at the Olympics. You wake up in your hotel bed, you didn’t sleep so great - how could you, with all this excitement - but it doesn't matter, because you’ve done the work and you’re at your peak.

You’ve deleted all social media from your phone, and only have a few apps open so your closest family can send you some supportive texts. You’ve also kept your health tracker app. Your recovery score is dismal. You brush it off, but it leaves a nagging thought in your mind, the smallest seed of doubt.

Tell me: is this ' empowering your day'?